Dof of a Rigid Body

Figure 2.2:

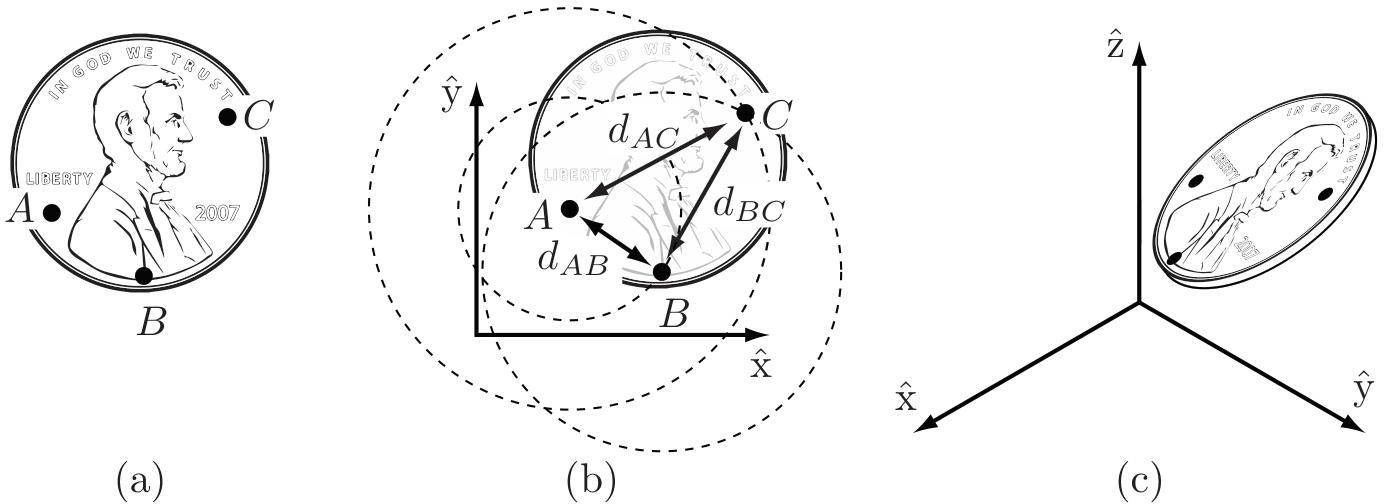

- (a) Choosing three points fixed to the coin.

- (b) Once the location of

is chosen, must lie on a circle of radius centered at . Once the location of is chosen, must lie at the intersection of circles centered at and . Only one of these two intersections corresponds to the “heads up” configuration. - (c) The configuration of a coin in three-dimensional space is given by the three coordinates of

, two angles to the point on the sphere of radius centered at , and one angle to the point on the circle defined by the intersection of the a sphere centered at and a sphere centered at .

Continuing with the example of the coin lying on the table, choose three points

To determine the number of degrees of freedom of the coin on the table, first choose the position of point

Once

Once we have chosen the location of point

In other words, once we have placed

Suppose that we choose to specify the position of an additional point

We have been applying the following general rule for determining the number of degrees of freedom of a system:

This rule can also be expressed in terms of the number of variables and independent equations that describe the system:

This general rule can also be used to determine the number of freedoms of a rigid body in three dimensions. For example, assume our coin is no longer confined to the table (Figure 2.2 (c)). The coordinates for the three points

- Point

can be placed freely (three degrees of freedom). - The location of point

is subject to the constraint , meaning it must lie on the sphere of radius centered at . Thus we have freedoms to specify, which can be expressed as the latitude and longitude for the point on the sphere. - Finally, the location of point

must lie at the intersection of spheres centered at and of radius and , respectively. In the general case the intersection of two spheres is a circle, and the location of point can be described by an angle that parametrizes this circle. Point therefore adds freedom. - Once the position of point

is chosen, the coin is fixed in space.

In summary, a rigid body in three- dimensional space has six freedoms, which can be described by

- the three coordinates parametrizing point

, - the two angles parametrizing point

, - and one angle parametrizing point

, provided , , and are noncollinear 非共线的.

Other representations for the configuration of a rigid body are discussed in Chapter 3.

We have just established that

- a rigid body moving in three- dimensional space, which we call a spatial rigid body, has six degrees of freedom.

- Similarly, a rigid body moving in a two- dimensional plane, which we henceforth call a planar rigid body, has three degrees of freedom. (This latter result can also be obtained by considering the planar rigid body to be a spatial rigid body with six degrees of freedom but with the three independent constraints

. )

Since our robots consist of rigid bodies, Equation (2.1) can be expressed as follows:

Equation (2.3) forms the basis for determining the degrees of freedom of general robots, which is the topic of the next section.